- Home

- Sanford Friedman

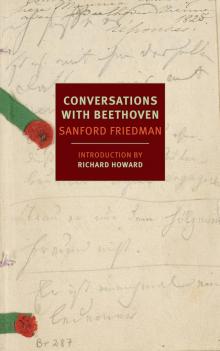

Conversations with Beethoven Page 16

Conversations with Beethoven Read online

Page 16

I praised Wawruch for the same reason.

He had no right to remark on future tappings. Where will it end!

There is only one answer: your brother must call in Malfatti.

Then take it upon yourself. Let us draft a note forthwith.

My dear Malfatti,

As you may have heard I have been confined to bed with dropsy since early December and in this connection have just undergone a second operation. Every day I hope to see an end to this trying illness, yet every day it persists. Unfortunately the doctor in attendance, a certain Professor Wawruch, has no prior knowledge of my constitution. Why, in the last five weeks alone I have been compelled to empty 75 bottles of some witches’ brew and to swallow God only knows how many different powders. He is ruining me with overmuch medicine! Although I have done my best to tolerate his treatment, frankly I have lost all confidence in the man. Thus I beg of you to come to my aid as soon as possible—Believe me, it is a matter of life and death.

Your most devoted

BEETHOVEN

Great Maestro, I’ll take it to him at once.

• • •

Great Maestro, I bring you back a disappointing reply.

He didn’t even condescend to write it. “Say to Beethoven that as a master of harmony he ought to know that I, too, must live in harmony with my colleagues.”

No mention was made of old wounds, only of his colleagues, naturally. Like all members of the medical profession, Malfatti’s first allegiance is to his colleagues.

Apart from his cultivated suavity, I found him quite severe and glacial. Indeed despite his southern heritage, he has every appearance of the Swiss. Perhaps he hails from the Italian side of the Alps.

I understand your bitter disappointment, yet tears are premature.

Because he didn’t close the door completely.

Surely his unwillingness to take Wawruch’s place doesn’t imply an unwillingness to consult with him.

Then let us try again, with fewer words and more flattery.

My dear Malfatti,

As the pre-eminent master of harmony I bow my knee to you, the pre-eminent master of the medical art, and ask only that you introduce an element of counterpoint in consultation with Dr. Wawruch.

With deepest respect I remain ever your most devoted

BEETHOVEN

• • •

Great Maestro, I bring you glad tidings! Malfatti agrees to consult with Wawruch and the others the day after tomorrow.

Goodness, tears when he won’t come and tears when he will.

True enough, there is every reason now to look for real improvement.

• • •

Esteemed Patient, my distinguished colleagues and I have concluded our consultation.

Seeing that Dr. Malfatti is an old friend of yours, he naturally appreciates far better than we your idiosyncrasies, in particular your decided taste for spirits. Thus I shall step aside for the moment while you learn from him the novel course of treatment he has hit upon.

Beethoven, you are more than kind. Still, you must not entertain such lofty expectations. In spite of my reputation for performing miracles, I am not Aesculepius.

No apologies are necessary. Although we have not exchanged a word in ten years, I bear you no ill-will. Do keep in mind that I am from the venerable city of Lucca, not from vengeful Corsica. Besides, ten years ago you had just been appointed your nephew’s guardian and had your hands full—Indeed from what I am told they are still so.

It is Dr. Wawruch’s opinion that much of your illness is due to the mental distress your nephew has inflicted upon you.

Not only at present but from the start; and indeed I thoroughly agree with him.

Seeing that I am pressed for time let me come to the point. Do you still enjoy a good Moselle?

Then let us do away with all those powders and medicine bottles that you so detest. In their place I have arranged for you to be given a very simple recipe: a daily glass of frozen punch.

By no means am I joking.

Nothing whatever, only the punch. Yet note well, you are not to drink more than one glass a day. If you abuse my orders, as is your wont, rest assured that you will come to grief. What is more, you are never to drink it in its liquid form, only frozen. In addition I have given orders for the abdomen to be rubbed with ice-cold water.

The object, in brief, is to tone up your digestive organs; at present they are utterly worn-out.

You will start the regimen today.

No, no, that is out of the question.

Quite simply because I have not the time to take on another patient.

Unfortunately the same is true of my assistants, all of us are overtaxed.

You should have thought of that ten years ago.

I cannot stay another moment, so let it be. If possible I shall look in on you occasionally. Meanwhile you are perfectly safe in Dr. Wawruch’s hands.

• • •

Dear Schindler,

Miracles! Miracles! Miracles! The highly learned professors are both defeated. Only through Malfatti’s practice shall I be saved! It is necessary that you come to me for a moment before noon.

B.

• • •

Great Maestro, the transformation is indeed a miracle. Not only has Malfatti toned up your digestive tract, but he has restored your spirits overnight.

The whole night through, without waking even once?

That in itself is a miracle.

How heartening it is to see the fire in your eyes again, to hear you speak again of your Saul & David oratorio.

Come now, it was Malfatti who prescribed the treatment—is that not enough?

Don’t make so much of his taking you back as a patient; to all intents and purposes you are his patient.

I’ll go to him if you insist, yet would it not be shrewder to wait and let him come to you, as he promised.

Even if he sends one of his assistants, at least the man will offset Wawruch.

Well and good, if Malfatti doesn’t visit within the week, rest assured that I will go to him.

But haven’t you already had your glass for the day?

In that case you cannot have another.

Benefits aside, you simply cannot have a second glass of punch.

I’ll thank you not to say that. The Spirit that Denies indeed! If anything, I am your guardian angel.

• • •

Great Maestro, it seems that the busy cadet found time at last to write.

IGLAU, JANUARY 13, 1827

My dear Father,

I have received your letter written by Schindler; I ask only that in future you include the date so that I can estimate the speed of the post. As for the state of your health, I am so happy to know that you are in good hands; I, too, had some misgivings about the treatment of your former (or perhaps still present?) doctor; I hope that from now on all will go well.

I wrote to Councilor Breuning some days ago and indicated the things that I still need. I would have written you directly, but I wanted not to tire you. No doubt the Councilor will attend to everything in the best way.

You wish to know my circumstances in detail. My captain is a thoroughly cultured man with whom I expect to get along very well. I share a nice room with the company sergeant-major, a very fine young man.—There is no such thing as an officer’s mess here; everyone goes to eat where he pleases. To economize I have already changed my eating place several times, but now a common mess for cadets is to be set up—if it is ever finished. Meanwhile in the evening everyone leaves the barracks to look for a place to eat. I have an orderly who takes care of me and receives 1 gulden a month, not counting small outlays for white lead and chalk to clean the uniforms. Washing also comes to a few gulden, if one wants it really clean. There is a theater here, too, to which I go with the captain’s permission.—These are more or less the ordinary circumstances that I am able to report at present.

Of the things that I requested from Councilor Br

euning and still need, the captain cannot supply anything without authorization, naturally; therefore I ask you to mention it to the Councilor. And if you would send me something extra to cover the unavoidable expenses that I have already explained to him, it would be most kind. What is more, I depended upon receiving my pay from the day that I enrolled (Dec. 12, 1826), but this has not happened because the enrollment roster remains in Vienna. Thus I must still watch every penny.

In conclusion one more request. A first lieutenant who loves music and especially your works, plans to perform the Pianoforte Concerto in B flat (Op. 19) at his quarters this week. However, by accident the flute part has been lost, and so he has turned to me. Hence may I ask you to arrange for the part to be sent to me as soon as possible.—Do not worry about my address; I receive letters in care of the regimental adjutant.—Write to me again very soon. I embrace you with all my heart. My regards to the Councilor.

Your loving son

KARL

P.S. Do not think that the little privations to which I am now subjected have made me malcontent. On the contrary, rest assured that I am happy here, and regret only that I am so far away from you. But with time that, too, will change.

As you see, I have treated myself to a seal with my name.

Great Maestro, it is one thing to watch every penny and quite another to treat oneself to theater and a name seal, etc.

That is for you to decide. However, before you send him anything, you ought to review your own accounts.

I am not suggesting that you are in arrears, except where Wawruch and Seibert are concerned, yet neither is the cashbox overstuffed. Besides, you have no way of knowing how much Malfatti will charge you for his services.

He may have come to you as your friend, but don’t assume for a moment that as your doctor he’ll depart without his fee.

I won’t wager with you simply because I don’t wish to take your money.

You stint yourself and yet would send your nephew 20 gulden!

Not even 10, seeing that you have no idea how he plans to spend it.

In that case I have nothing more to say. I’ll do my best to hunt down the flute part this afternoon and post it together with the money in the morning.

• • •

Esteemed Patient, is the neck merely stiff or is there pain?

I am somewhat confused. Are you speaking of Saul and the Witch of Endor, or of Aeneas and the Sybil of Cumae? It would seem that you compound the two.

Confound the two?

Medical practitioners? I don’t follow you.

If one is not to tell it in Gath, then it must be Saul.

Ah! But therein lies the confusion: Samuel is summoned up by the Witch of Endor, whereas Aeneas is directed down to the underworld by the Sybil.

He descends in order to behold his father—ire ad conspectum cari genitoris et ora

Mother? In that case you have confused Aeneas with Odysseus; it is Odysseus who descends in search of his mother.

Plutarch?

Please excuse me for a moment.

Your housekeeper informs me that you took more than one glass of punch yesterday, nay, not only yesterday but the day before.

Do not blame her; the moment you mentioned your neck pain and I heard you wander in your speech, I suspected something of the sort.

I shall put it to you plainly: if you continue to abuse Dr. Malfatti’s orders, I fear that it is Beethoven who will end in the underworld.

• • •

JANUARY 19, 1827

My Great Maestro!

Since I have a rehearsal today at half past eight and cannot possibly afford to miss it, I must report in writing the upshot of my second visit to Malfatti.

He will come to you this morning at half past nine. Knowing perfectly well that Wawruch has a lecture until ten, I told Malfatti that we were also inviting the Professor to come at half past nine. In order that we don’t get into a pickle you need only say to Malf. that you did not learn until today that the Professor’s lecture prevented him from coming before ten. For his part Malf. has a meeting in the city at ten; thus you finally have your opportunity to speak to him alone.

Since, however, the past still rankles him somewhat, I would ask you to patch things up completely; why, only today he gave me to understand that he could not forget your “calculated offense,” as he called it.—Some artful words from you will put everything to rights and restore the status quo.

Around two o’clock I shall have the honor of being with you again. Meanwhile summa cum reverentia

Your obliging

ANT. SCHINDLER

• • •

Beethoven, both the diarrhea and the Kolik are brought on by the cold fomentations—I shall give orders to discontinue them at once. However, the rest of your complaints, namely, the neck pain, the rattle when you breathe, the hoarseness, the stupor etc., those are of your own making. Thus I shall also give orders to cancel the frozen punch.

Because you are abusing the prescription.

On the contrary it is clearly harming you.

Nonsense, you have never done as you were told and never will. Of all the patients I have treated in my lifetime you are the most unruly, to say nothing of the most offensive.

Was it not offensive to represent me, the pre-eminent physician in Vienna, as not only stupid but dishonest?

Rubbish, you retailed it all over town!

The charge of stupidity was easily dismissed. But what of the trumped-up dishonest? People had no idea what you were aiming at, of what I was accused. Nor, God knows, did I. How dared you defame me in that fashion!

Kindly spare me talk of friendship—In what way dishonest?

In what way I ask!

Answer me! Did you suppose that I was after your gold ducats from the Philharmonic Society?

Claptrap! The man came all the way from London to be treated by Malfatti, not to chat with Beethoven. Your name was utterly unknown to him until it passed my lips. Indeed it was only through my good office that he even heard your music played.

So much then for my alleged dishonesty. Yet even that I might have stomached, had you but spared me your final affront.

Is it possible to forget such a filthy epithet?

The word you used was wily— “wily Italian.”

In that case I’ll enlighten you—Turks are wily, Italians are ingenious!

Nettled understates it, I was enraged! I cursed and damned your miserable heart! Had you been near me, I would have cut your throat! In lieu of that, I swore by the Almighty that I would never speak to you again, never tip my hat to you, never acknowledge in any way that you had been born—So, as you see, I have broken my holy vow by coming here.

Never mind how close we once were, on no account do I wish to patch things up.

My object, indeed my sole object in coming here was to settle old scores.

I shall do as I said, stop by from time to time; if you expect more, you will be sorely disappointed.

Very well, the prescription will be maintained, but only so long as you obey my orders. And don’t for a moment assume that Malfatti can be hoodwinked by the likes of you—a crude double-dealing Austrian!

• • •

Esteemed Patient, although the testes are somewhat retracted, there is no cause for alarm. Of more immediate concern is the blood you observed.

And prior to that was there blood in the stool?

Only a trace?

Is your appetite still so poor?

I begin to suspect that the seat of the trouble is the liver.—But the liver aside, it is now clear that another operation is needed.

Naturally, not only have I discussed the matter with your Dr. Malfatti, but also with Dr. Seibert, and both agree that it must be performed.

To the best of my knowledge the prescription is still in force—you will continue to receive one glass per day. However, I should tell you in candor that the frozen punch is not having the desired effect.

On the contrary

, if it were, there would be no need for a third operation.

Come now, there is no reason to hang your head. In all the world there could not be a more distinguished group of doctors than those assembled here for you. If any practitioners of the art can bring about a happy result, we can.

Trust in us.

• • •

Great Maestro, Wawruch gave me to understand that Seibert has already reported the results to Malfatti.

Now that the operation is over, one would think that Malfatti himself could find the time to look at the liver and belly.

There has been no word from him. However, Seibert plans to examine you once more today.

Perhaps he wishes to see if the fluid is passing through the liver. Evidently the liver is the key to the whole business.

To be on the safe side Seibert should be sent for at 5 o’clock.

For one thing to inform you of his findings, for another to give Malfatti the most thorough report possible.

Now for a different matter—A note has come from the soprano Schechner; it so happens that her father, too, once had dropsy.

The point is that the man was ultimately cured.

I have no idea. In any case I said that I would stop by and see the mother this afternoon.

If she tells me anything pertinent, I’ll report back to you.

• • •

Great Maestro, I have just come from Madame Schechner’s. Not only was her husband cured, but he was over 70 at the time!

Conversations with Beethoven

Conversations with Beethoven