- Home

- Sanford Friedman

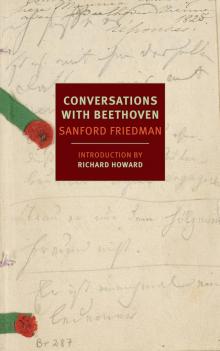

Conversations with Beethoven Page 15

Conversations with Beethoven Read online

Page 15

I may be an asinus, but I’ll wager that you won’t find a barber to shave you tomorrow for all the tea in China.

Because it’s New Year’s Day. You have waited three weeks, you can wait a day more.

How much are you prepared to pay the man?

In that case I’ll do my best to find one.

• • •

Uncle, I had all but forgotten what you look like without a beard.

Well now, tell me what you think of it.

Not of the shave but of the uniform; you haven’t said a word.

Apart from the tip, I’m glad that it pleases you.

Unfortunately there is no way around it; if I hadn’t tipped him, it wouldn’t fit me properly.

True enough, but what matters is that it does fit.—Now try to finish up the pancakes so that Sali’s feelings won’t be hurt.

Even so, do try; you hardly touched the soup.

Without the beard it’s obvious how much weight you’ve lost. Let’s hope that your appetite improves in the new year.

All the same I shall worry about you while I’m away.

But that’s a different matter; there is no reason for you to worry about me.

The training is merely routine. Believe me, I shall be in no danger at Iglau.

Please don’t turn your face to the wall, not tonight, I mean my last night in Vienna.

Would you like me to step out a moment?

Then tell me, if you will, what makes you grieve so.

That is foolish, of course you will see me again.

Premonitions aside, the moment I’m granted a furlough, you have my word

If that is not your chief concern, what is?

Who will take care of me when?

I don’t follow you—Do you mean who will take care of me after you leave this life?

Why then I’ll take care of myself, naturally.

You must not worry about such things. Surely if I’m old enough to serve in the military, I’m old enough

Only in your eyes am I still a boy.

I realize that I haven’t attained my majority; nevertheless I am 20 years old.

Dear Uncle, please don’t worry; somehow I shall find my way.

I don’t use “Father” for the simple reason that I am not your son.

On the contrary you have treated me with devotion and unstinting generosity. For that you have my deepest gratitude.

It goes without saying that you also have my love.

Why do you disparage a nephew’s love? Is it ipso facto inferior to a son’s?

What matters is the sentiment, not how I address you.

Firstly, if you were in truth dying, you may be sure that I would stay; secondly, in no wise am I deserting you, I am simply doing my duty.

But even if I were your natural son, I

By no stretch of the imagination am I your “bodily son”—Yet even if that were the case, I should be obliged to leave for Iglau.

As for filial piety, forgive my impudence but when your own father died you did not return for his funeral.

Nor did I say that you beat me. Why do you speak of beatings?

Please don’t remove your night shirt. I would hardly be able to see the bruises at any rate, inasmuch as your father laid those blows upon you fifty years ago.

Naturally you continued using that form of address; in spite of the blows he was still your father.

I don’t deny that you are mine—in all but body.

Nothing makes me hesitate; if you wish, I’ll gladly call you Father.

I’m not aware that I rubbed my temple.

Of course I don’t hold you to blame for what happened, at least not in retrospect. After all, the wound was self-inflicted.

Why do you grieve again—don’t, I entreat you.

What reproaches?

But they are long forgotten. Besides—Who knows, perhaps I deserved your reproaches.

Please now, no more grieving.

Since there is hardly a scar to speak of, I would prefer not to.

If it doesn’t concern the scar, why do you ask me to lower my head?

Ought I to go out to the flock like Jacob and fetch a goatskin?

Forgive me, I was only joking. In truth I would welcome, nay, cherish your blessing.

O thank you—I don’t—I—thank you.

Indeed I’m not too old to be kissed.

And you, are you too old?

Rest assured that I shall write you regularly.

Now I must say good-bye. May the New Year bring you full recovery and the glorious completion of your Saul & David oratorio.

Farewell, Uncl my dear Father.

• • •

5

GREAT Maestro, not only am I flattered by your willingness to take me back, but I am eager to prove myself worthy of your trust.

Is Dr. Bach’s address unchanged?

VIENNA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 3, 1827

Esteemed Friend!

Before my death I declare that Karl van Beethoven, my beloved nephew, is the sole heir to all my property, including, chiefly, seven bank shares and whatever cash may be available—Should the laws prescribe alterations pertaining to this bequest, then try to turn them so far as possible to my nephew’s advantage—I appoint you his trustee and ask you together with his guardian, Councilor von Breuning, to be a father to him—May God preserve you—A thousand thanks for the love and friendship you have shown me—

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Great Maestro, are there no provisos?

Some stipulation which would prohibit the mother from laying her hands on anything.

You would do well to ask Dr. Bach if “sole heir” suffices. As for your nephew, would it not be wise to impose certain limitations?

On his behavior, naturally. Considering his love of gambling and café life, I venture to say he’ll run into debt unless you rein him in.

A mistake about what?

By no means have you made a mistake where I am concerned.

Forgive me, in future I’ll keep my views of your nephew to myself.

I have already said that I’ll keep them to myself, what more do you wish? Come now, do relent.

I beg you to relent.

But if you send me packing, who will you find to take my place? Surely not your worthy brother.

You cannot be in earnest.

But young Breuning is hardly capable of

As you wish, I’ll fetch him for you now. Before I do, however, you may rest assured that in all Vienna, not to mention the whole Imperial State, there is not a single schoolboy, no matter how bright (which this one is certainly not), who has the requisite skills, patience and, I may say, fortitude to take my place.

• • •

Prospero, how are you feeling?

Father, too, is about the same.

He is well enough to read a letter.

I don’t know if he is well enough to reply.

I’ll tell him that you would welcome his opinion, if it’s no trouble.

I left Schindler in the entrance hall.

I’ll send him to you.

• • •

Well, Great Maestro, are you satisfied with your new amanuensis?

Oh? And may I ask the nature of your reservation?

I’m not at all surprised, few children nowadays are able to spell; they think only of dancing and playing billiards. Yet if young Breuning won’t do, who is to take my place?

Thank you, I’m pleased to resume my duties.

The letter is on the bedside table.

In that case I’ll retrieve it from Breuning after dinner and ask if there is a reply.

• • •

Dearest Friend!

I am still too weak to write you at length, but I think that a few candid words from the heart should be spoken. Since through Gerhard you have asked me to read the letter to Dr. Bach, I have done so and return it to you for the time being with the following observations: that you name Karl as heir in the event, which I

hope is far off, that you leave this life, is appropriate considering your way of thinking and what you have already done for him. But up until now Karl has shown himself to be very reckless, and one doesn’t yet know how his character will develop. Thus I would recommend that for his own good and for his future security you limit his power to dispose of capital either for life or at least for a few more years, until he turns 24 years, the age of his majority. In any case he would have enough annual income on hand and the limitation would protect him from the consequences of reckless actions before he reaches maturity. Speak of this with Dr. Bach from whom I should think a visit would be helpful. He will arrange everything in the simplest way; I would welcome the opportunity to talk with you or with Dr. Bach about my observations, for I fear that a mere time limitation will not keep Karl from contracting debts which he would only have to pay subsequently from his eventual inheritance.

I embrace you warmly.

STEPHAN

• • •

Worthy Friend, although I agree with Councilor Breuning that Karl’s behavior last year was reckless, I’m not convinced that you should limit his freedom to dispose of the capital. From your letter to me it’s clear that you have no such object in mind. Hence I would advise you to follow your heart and impose no limitations.

The notion of controlling Karl’s behavior from beyond the grave strikes me as harsh. What happened last year was not extraordinary: many young men of Karl’s age are inclined to play billiards, gamble and even to attempt suicide—God be thanked he did not succeed. Besides, I suspect that such behavior is now behind him.

I realize that you had the highest hopes for him, yet he is not without merit—indeed he is altogether intelligent, affable and conscientious. Added to that, he is devoted to you.

I truly doubt that he is more devoted to her.

The only way to prevent his mother from receiving any portion of the capital is to hold it in trust; therewith you could stipulate that the interest will go to Karl for the rest of his life and the principal pass to his legitimate off-spring after his death.

You need not decide the matter now, there will be plenty of opportunity

Do not despair; the grim reaper is still far off.

A trocar and a scythe are hardly equivalent. Has the surgeon said when it will be performed?

Since tomorrow is Friday, it will likely be sometime next week.

No more of that. Not only will you survive the operation, but you will go on to finish your tenth symphony.

It’s no trouble, believe me. If I’m obliged to lecture on the day of the operation, then I’ll come here immediately afterwards.

May God be with you, my friend.

• • •

Brother, I cannot help but agree with Breuning.

I’m surprised that Dr. Bach holds the opposite view—No doubt that is because he has had so few dealings with our nephew.

I’m thinking of neither the gambling debts nor the goings-on at Gneixendorf, but of Karl’s devotion to his mother—Have you considered the possibility that he might predecease her—God forbid!

Nevertheless, now that he is in the military there is no telling what might happen. In my opinion you ought to create a trust.

Well, if Dr. Bach said the same, that should settle it.

What others? You’ve already consulted with everyone worthwhile—everyone, that is to say, but Wolfmayer.

What on earth for? Holz is a connoisseur of wines not of business dealings.

Well and good, if I happen to see him, I’ll mention

But surely it can wait until Monday.

In that case I’ll stop by the Chancellery now and ask him to visit you tomorrow.

• • •

Prospero, how are you this morning?

Has your stomach become smaller?

Then the surgeon shouldn’t delay.

Has your appetite improved?

By now you should be eating meat.

Have you been given an enema?

You should be given more of them.

Have you finished reading Walter Scott?

Would you like to read Schiller?

Perhaps you’d like Sommer’s travel sketches.

Doctor amo amas amat has just arrived; he is taking off his coat.

Don’t speak so loudly or he’ll hear you. Father, too, considers him a bungler.

I must go now. I’ll bring you the Sommer tomorrow.

• • •

Esteemed Patient, be so good as to turn over.

But if you turn your back on me, I cannot examine you.

Unless I examine you, I cannot consult with Dr. Seibert.

Without consultation we cannot determine when next to tap the water.

Tomorrow seems premature; I am still inclined to wait.

Because the moment it is tapped, the water reaccumulates. Besides, this cold rainy weather only aggravates the dropsy. Thus I think it best to delay as long as possible.

Since the tappings are in no wise a cure, you are not incorrect to call them a palliative, albeit a necessary one. Nor can I deny the possibility of future tappings.

Your argument is indisputable. The Romans, as you doubtless know, deemed logic the art of arts. I may, therefore, reverse my judgment and recommend that Dr. Seibert perform the operation this coming week.

• • •

Great Maestro, for weeks and weeks I’ve tried to persuade your know-it-all brother to call in Malfatti for consultation, but to no avail. Yet as much as I value Malfatti, you must not lose faith in Wawruch; after all, he has done a great deal already.

In spite of your antipathy to him, Wawruch is regarded as an able man, esteemed and appreciated by his students. Although I can’t speak from experience, I myself have considerable confidence in him.

Even so he has a thorough understanding of his profession, that is well known.

For him to speak of the possibility of a third operation is quite different from his regarding it as inevitable. Don’t always look on the dark side.

Since there is time before my rehearsal let us deal with the letter to your nephew.

My dear Son!

It is clear now that the two learned gentlemen have a second operation up their sleeve; all that remains to be decided upon is the date.

Great Maestro, excuse me a moment.

Sali says that Holz is here. Oddly enough, I saw your Mr. Holz just yesterday and gave him a good piece of my mind.

Because I heard from someone that he doesn’t like my coming here. I called him to account for that.

Holz insisted that he had said nothing of the kind and felt no jealousy where I am concerned. Further, he told me that he must divide his time between his office, his lessons and his bride; hence he cannot come to see you. Yet lo and behold, here he is! Clearly the man is not to be trusted.

I told him to wait, naturally.

How was I to know that you had sent for him? I’ll fetch him at once.

Maestro, forgive me for neglecting you these last few weeks, but lately I find myself without a moment to spare.

Would that my duties were confined to the bedroom. Unfortunately they take me to the office, the quartet, lessons, etc. Nor do I see any respite in sight.

Great Maestro, far from “lurking about,” I am waiting for you to finish the letter to your nephew.

If you wish me to step out for a moment, you need only say so.

Indeed I have no objection, so long as you understand that if I leave for the day, the letter will not—Or do you plan to have Mr. Holz do the job in my stead?

I take you at your word. Meanwhile I shall wait to hear from you. Good day.

Goodness, Maestro, seldom have I seen such a puffing of the breast, such searching looks and darting glances—Yet you surely didn’t send for me just to goad Schindler.

Although I know there is a secret drawer, I have no idea of its whereabouts.

I can imagine why you might wish to keep your brother in ignorance,

but not why you wish to reveal it to me. Seeing that Breuning is your closest friend, wouldn’t

I hadn’t heard he was ill. In that case I’ll bear the burden, albeit reluctantly, providing that you promise to live another twenty years.

• • •

Esteemed Patient, owing to Dr. Seibert’s customary skill the second operation is now successfully behind you.

Do you still feel much pain?

Aurelius himself could not have borne it more stoically.

The water was clearer today, a good sign.

Twice as much as last time, almost six gallons.

If another operation should become necessary, I shall certainly not look for twelve. Now please drink this.

Regardless of how much you hate medicine, it is critically important to take it after an operation. Vincit qui se vincit

But it is for your own good.

Sometimes I wonder which of us is the doctor, which the patient.

Do try to rest quietly.

• • •

Great Maestro, now that it’s over, I must confess that I often feared you would choke before they made up their minds when to operate.

I kept it to myself because I didn’t wish to dampen your spirits.

Conversations with Beethoven

Conversations with Beethoven