- Home

- Sanford Friedman

Conversations with Beethoven Page 12

Conversations with Beethoven Read online

Page 12

After supper I had no difficulty persuading you to get into the bed; you did so with alacrity. Whereupon I spread all three blankets over you and sat down at the table. About ten o’clock you started coughing violently and groaning with pain, but by and by the fit subsided, indeed you even dozed. It was not long, however, before the coughing resumed; worse still, you complained of a hellish thirst. Unfortunately the water in the room was ice-cold, hence I went to fetch another jug from the proprietor. When I knocked at his door there was no answer, so naturally I knocked again. Yet no matter how many times I knocked, he did not answer. Clearly the villain was feigning sleep, for even after I gave the door a swift kick he did not stir.

Upon returning to the room I found you at the table with a cup in one hand and the jug, already half-empty, in the other—notwithstanding the ice-cold water, you had got up to slake your thirst. As you were still coughing I begged you to get back into the bed, but you refused. Nor would you relinquish the jug. Indeed you clasped it to you defiantly and sat down at the table. There being but one chair in the room I covered you with the blankets from the bed and stretched myself on the crude mattress. In spite of the cold I, too, must have dozed for suddenly something woke me with a start. It was the jug which had slipped from your hands and broken. When I stooped to gather up the pieces there was scarcely a drop of water on the floor; you had, alas, quaffed it all. An instant later the proprietor’s wife was at the door demanding to know what had broken. Thus it became my turn to feign sleep. Soon thereafter, your teeth began to chatter and your limbs to shake, nay, your whole body shook, shook indeed so violently that the chair which you gripped with both hands thumped the floor. In vain did I put my frock coat over you—all the coats in the Austrian state could not have warmed you.

At dawn the proprietor’s wife brought the breakfast: a cup of water and a slice of bread for each of us. Since I did nothing to conceal the jug, she was quick to spy the pieces. The husband, to be sure, was even quicker; in recompense for the breakage he demanded 1 gulden, 20 kreuzer. Imagine! for an earthen jug. Needless to say that I refused to pay such an exorbitant sum, nor would I be bullied.—Thus he sent for the police! In no time an officer appeared. After making your name known to him, I told the man what miseries you had suffered at the hands of the proprietor; what is more, I told him that you planned to register a complaint with the Viennese authorities. Thereat the officer laughed in my face! I was affronted, until it came out that the man had in fact heard of you. “What do you take me for, an imbecile?” he said. “Surely a composer of such renown doesn’t travel by farm wagon!” Thus in the end I paid the cursed sum and we continued on our way.

The second leg of the journey proved even worse than the first, not merely because you were feverish, but because every jog along the way and every fit of coughing brought fresh pain.

We arrived here last night shortly after 9 o’clock.

• • •

Uncle, the maid has finally returned. Braunhofer regrets that he cannot come.

Let’s send for Staudenheim.

I’ll go myself this time.

• • •

Uncle, Staudenheim assures me that he’ll visit you this evening.

• • •

Uncle, Councilor Breuning is waiting in the entrance hall; if it doesn’t overtax you, he would like to come in for a moment.

Ludwig, are you feeling any better?

Don’t tire yourself, your nephew has told me what happened at Mitterndorf. But why, if you arrived two days ago, did no one inform us?

Gerhard has been practicing as zealously as young Liszt; he is most eager to show you his new technique. But first we must find someone to look after you. According to your nephew, Dr. Braunhofer excused himself and Dr. Staudenheim failed to appear.

I’ve been thinking of Dr. Malfatti.

I realize that you quarreled years ago; all the same, it’s my opinion that you should send for him.

Frankly I don’t see why you would turn to Holz. It’s unlikely he knows of a doctor that you yourself have not considered. Still, he may have heard of someone on the staff while your nephew was in the hospital.

By all means do what you think best. Meanwhile I’ll arrange as soon as possible to present your nephew to the Lieutenant Field-Marshal.

Don’t upset yourself; it needn’t be done today, yet neither should we delay too long.

I must go now, but I’ll stop by tomorrow. May God be with you, my friend.

• • •

No, Uncle, I didn’t mislay the note to Holz; it was you who put it aside. However, I’ll be glad to take down another.

Official Majesty!

I wrote to you immediately after my arrival which took place a few days ago. But the letter was mislaid. Then I fell ill, and so ill that I think it is wiser to stay in bed—Hence I shall be greatly delighted if you will visit me.

Ever your friend

BEETHOVEN

• • •

Maestro, I’ve had Professor Wawruch sent for.

No, I don’t know him personally, but he is said to be one of the most skillful doctors in Vienna.

He is professor of special pathology and medical clinics at the general hospital—where, by the way, his father-in-law is the Director.

He’ll come to you after dinner, about 3 o’clock.

• • •

Esteemed Patient, I am Prof. Wawruch, one who truly reveres your name and will do everything in his power to give you swift relief. Satis verborum

Uncle, in order to facilitate the examination I’ll take down the questions.

Do you suffer from hemorrhoids?

When was the last bowel movement?

Take a deep breath.

Since when is the abdomen so swollen?

How often do you urinate?

Without difficulty?

The feet were never greatly swollen?

Have you ever seen blood in the stool?

Only in the sputum?

Catch your breath before you speak.

Don’t speak yet.

Be calm or you will choke.

Esteemed Patient, it is clear that you are suffering from a serious inflammation of the lungs.

Do put aside all thought of your mother and brother; the cough is not a symptom of consumption but of pneumonia.

Rest assured that it will not finish you off while Prof. Wawruch is your doctor. Your farm wagon may have brought you to death’s door, but thereabouts I am the gatekeeper; as a practitioner of the medical art it is I who shall finish off the illness. Experto credite

I shall order forthwith the necessary medicines to commence a vigorous counter-treatment.

• • •

Uncle, Dr. Wawruch says, aegrescit medendo.

I’m only joking. He said that if you don’t have a bowel movement in the course of the day, you ought to be given an enema tonight.

I’ve already told the maid that if there is nothing by 7 o’clock, she is to fetch the barber.

Because he knows how to do it properly. What is more, he has syringes.

Wawruch found you somewhat better than yesterday. Even so, he would have you remember that every drop of urine must be saved.

So that he can gauge not only the quality but the quantity. I’ve given orders to buy a bedpan and a urinal. He says that the former is very comfortable and will keep you from growing so cold. He wants you to stay warm at all times. Even at night when you wake, you are to be given warm compresses. Thus someone must be near you at that time.

For a few days at most, during which the maid could sleep in here or in the entrance hall.

Since she and Sali are here at night, I see no reason for me to stay as well. Besides, you know that I promised my mother to stay with her until I leave for Iglau.

That depends on when I’m presented to the Field-Marshal.

Councilor Breuning expects to speak to him today.

• • •

Ludwig, the Lieutenant Fie

ld-Marshal has agreed to meet your nephew on Sunday.

In no wise precipitate, we have already delayed three months.

Assuming that all goes well, your nephew will then have to be fitted for uniforms, given a physical examination, swear the oath of service, etc. Altogether the procedure takes about a week.

Frankly I would not count on his being with you for the holidays.

But if we put it off again, I fear there will be no cadetship.

Do not give in to despair. According to Dr. Wawruch—the doctor aside, I’m able to see for myself how much better you are today.

The cases are not alike. When you nursed your mother she was dying of consumption, whereas you are being treated effectually, thank God, for pneumonia.

Naturally I remember how many weeks you sat at her bedside; the differences between you and your nephew are only too obvious. But then he is not your son.

You have indeed shown yourself a devoted father to him. I mean rather that you were your mother’s natural son—Unless, of course, you are still disinclined to acknowledge the fact. Are you?

Not just gossip. My sister Lorchen told me that she and Wegeler wrote you last year raising the selfsame question, yet they never received a reply.

No, it’s not too late; surely they would still welcome a letter.

I misunderstood you.—Too late for what?

But it was after 7 o’clock when I arrived.

I’ll go and ask her.

Sali says that the maid has already gone to fetch the barber.

Vexatious, to be sure, but you’ll feel much better afterwards.

At least you’ll sleep more comfortably. Good night, my friend.

• • •

VIENNA, DECEMBER 7, 1826

My Beloved Old Friend!

Words fail me to express the pleasure which your letter and Lorchen’s have afforded me. And indeed an answer should have been sent off to you as swiftly as an arrow. But on the whole I am rather slack about writing letters, for I believe that the best people know me well in any case. Often I think out a reply in my head; but when it comes to writing it down, I usually throw away my pen, simply because I am unable to write as I feel. I remember all the love which you have always shown me, for instance, how you had my room whitewashed and thus gave me a pleasant surprise,—and likewise all the kindnesses I have received from the Breuning family. Our drifting apart was due to the changes in our circumstances. Each of us had to pursue the purpose for which he was intended and endeavor to attain it. Yet the eternally unshakeable and firm foundations of good principles continued to bind us strongly together.—Unfortunately I cannot write to you today as much as I should like to, for I have to stay in bed. So I shall confine myself to answering a few points in your letter.

Uncle, what Wegeler asks in effect is why you haven’t defended your mother’s honor.

Evidently an article in the standard encyclopedia asserts that you are a love-child who was fathered by the King of Prussia.

You say that I have been mentioned somewhere as being the natural son of the late King of Prussia. Well, the same thing was said to me a long time ago. But I have adopted the principle of neither writing anything about myself nor replying to anything that has been written about me. Hence I gladly leave it to you to make known to the world the integrity of my parents, and especially of my mother.—You mention your son. Why, of course, if he comes to Vienna, I will be a friend and a father to him; and if I can be of any use to him or help him in any way, I shall be delighted to do so.

I still possess Lorchen’s silhouette. So you see how precious to me even now are all the dear, beloved memories of my youth.

As for my diplomas I merely mention that I am an Honorary member of the Royal Scientific Society of Sweden and likewise of Amsterdam, and also an Honorary Citizen of Vienna. A short time ago a certain Dr. Spiker took with him to Berlin my latest grand symphony with choruses; it is dedicated to the King, and I had to write the dedication with my own hand. I had previously applied to the Legation for permission to dedicate this work to the King, which His Majesty then granted. At Dr. Spiker’s instigation I myself had to give him the corrected manuscript with the alterations in my own handwriting to be delivered to the King, because the work is to be kept in the Royal Library. On that occasion something was said to me about the Order of the Red Eagle, Second Class.

Uncle, it was ten weeks ago; I remember because we departed for Gneixendorf the following day.

All that Spiker said is that H.M. looks upon you with favor, nothing more.

It makes no difference anyway since Spiker resides in Berlin; here you would have to approach Prince Hatzfeld at the Embassy.

Surely you are in no position to prod the Prussian Ambassador.

Let’s not argue the point.—Sali has made a batch of walnut cookies. Would you like some with your tea?

It would be better to have the tea first and then finish the letter. You shouldn’t overtire yourself.

• • •

Uncle, a packet has arrived from the Prussian Embassy. Imagine! Had we not been alone yesterday, I would assume that our every word was reported to Prince Hatzfeld.

There are several letters, but doubtless you will find the one from the King of particular interest.

BERLIN, NOVEMBER 25, 1826

To the composer Ludwig van Beethoven,

In view of the recognized excellence of your compositions I was greatly pleased to receive the new work which you have dedicated to me. I thank you for sending it, and send you the accompanying diamond ring as a token of my appreciation.

FRIEDRICH WILHELM

Uncle, how good it is to hear you chuckle.

The ring is not enclosed.

Don’t jump to conclusions; perhaps Hatzfeld is waiting to hear from you.

I still have time, provided the letter is brief.

Sir!

I send you my warmest thanks for the letters you have forwarded me. But I must ask you to be so kind as to send me the ring which H.M. the King of Prussia has decided to give me—I am very sorry that an indisposition prevents me from receiving in person this token (which is so precious to me) of H.M.’s love of art. I should be very reluctant to have it entrusted to the hands of a stranger—At the same time I request you to inform me in a few lines whether the worshipful Ambassador would be so kind as to take charge of a letter of thanks to H.M. the King and to arrange for him to receive it.

Uncle, you are right, that would prove embarrassing. On second thought you had better wait and see if the ring arrives. Meanwhile I’ll post the letter to Wegeler.

Why do you hesitate?

But you’ve already had a year to reflect upon the matter. Do let me post it.

Suit yourself, I must leave now.

• • •

Uncle, this just came.

GNEIXENDORF, DECEMBER 6, 1826

My dear Brother,

I am terribly sorry that you had such a miserable journey home. Had you but listened to me—However, that is water under the bridge. I do hope that you are recovering apace and will soon be enjoying better health. Unless something unforeseen occurs I shall be with you this coming Sunday.

Your devoted brother

JOHANN

No, Uncle, tomorrow is Sunday. Your brother will be pleased that I’m finally presented to the Field-Marshal.

Tomorrow at noon. Have you forgotten?

For Heaven’s sake! On what grounds would you have me cancel it?

But you are better every day. Wawruch says that you are out of danger.

I am in no danger.

You alone hold that opinion; others don’t view a career in the army as tantamount to throwing one’s life away.

My friend Niemetz doesn’t deserve such criticism.

He exercised no influence whatever upon me, pernicious or otherwise; I made the decision entirely on my own.

I’m not apt to change my mind.

You are mistaken if you think I’ll live to regr

et it. On the contrary I’m impatient to be inducted so that I can get on with my life.

• • •

Uncle, the Field-Marshal was extremely cordial, indeed he could not have been kinder. At the end of the interview he told me to come and see him again before I leave for Iglau.

Councilor Breuning remained behind for a moment.

Although the Field-Marshal spoke in passing of the hernia operation, not a word was said about the scar.

The induction ceremony will take place on Tuesday; thereafter I’ll be here another five or six days.

Unfortunately you are not well enough to come with me to the ceremony.

To Iglau! But that is impossible. Even if you regain your strength completely, Wawruch has told me that you are not to leave the house next week. Thus it goes without saying that he won’t permit you to travel to Iglau.

Because it takes two days which, I need hardly remind you, entails spending the night at a village inn. It’s simply out of the question.

Excuse me, there is someone at the door.

Both Breuning and your brother are waiting. Shall I fetch the Councilor first?

• • •

Ludwig, your brother tells me he has just arrived in town, so I’ll stay but a moment.

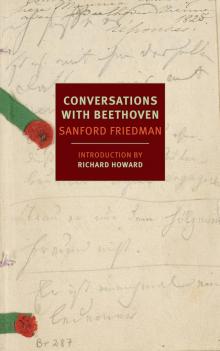

Conversations with Beethoven

Conversations with Beethoven